The U.S. conceded it won’t be able to stop completion of the controversial Nord Stream 2 natural gas pipeline from Russia to Germany, acknowledging the failure of a years-long effort to head of a perceived threat to European security.

The massive $11-billion project is just weeks away from completion and has led President Donald Trump to call Germany “a captive to Russia.” He has criticized the European Union for not doing more to diversify imports away from the nation that supplies more than a third of its gas.

Senior U.S. administration officials, who asked not to be identified discussing the administration’s take on the project, said sanctions that passed Congress on Tuesday as part of a defense bill are too late to have any effect. The U.S. instead will try to impose costs on other Russian energy projects, one of the officials added.

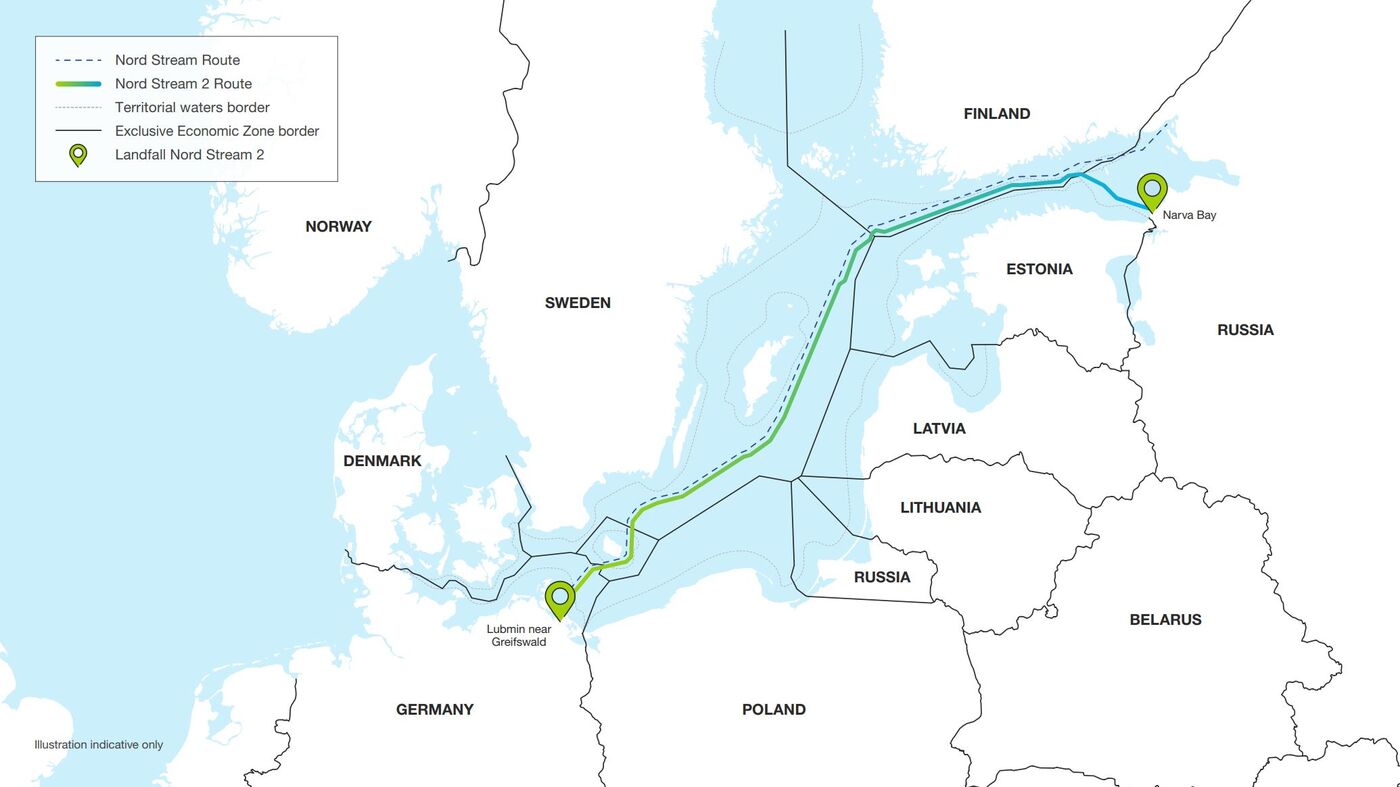

Nord Stream 2 is being laid on the bottom of the Baltic Sea to feed gas from Russia into Germany.

Source: Gazprom

The admission is a rare concession on what had been a top foreign-policy priority for the Trump administration and highlights how European allies such as Germany have been impervious to American pressure to abandon the pipeline. It also shows how the U.S. has struggled to deter Russia from flexing its muscles on issues ranging from energy to Ukraine to election interference.

“It has been a commercial project, but with a huge geopolitical dimension attached to that,” Peter Beyer, who is German Chancellor Angela Merkel’s trans-Atlantic policy coordinator, told Bloomberg Television in an interview in Berlin on Wednesday. “I’m expecting that the sanctions, if Donald Trump is going to sign that bill, will not have a big effect on that project.”

The administration is hoping to sharpen its focus on Russia when Deputy Secretary of State John Sullivan, who was confirmed as ambassador to the country last week, heads to Moscow next month. The post has been vacant since early October, when former envoy Jon Huntsman stepped down, and ties between the two countries have only continued to sour.

On a visit to Poland in February, Secretary of State Michael Pompeo said the Nord Stream 2 project “funnels money to Russians in ways that undermine European national security.”

Trump has indicated that he’ll sign the legislation passed Tuesday. The penalties on companies building the project, led by Russian energy company Gazprom PJSC, would be effective immediately, according to a Senate Republican aide.

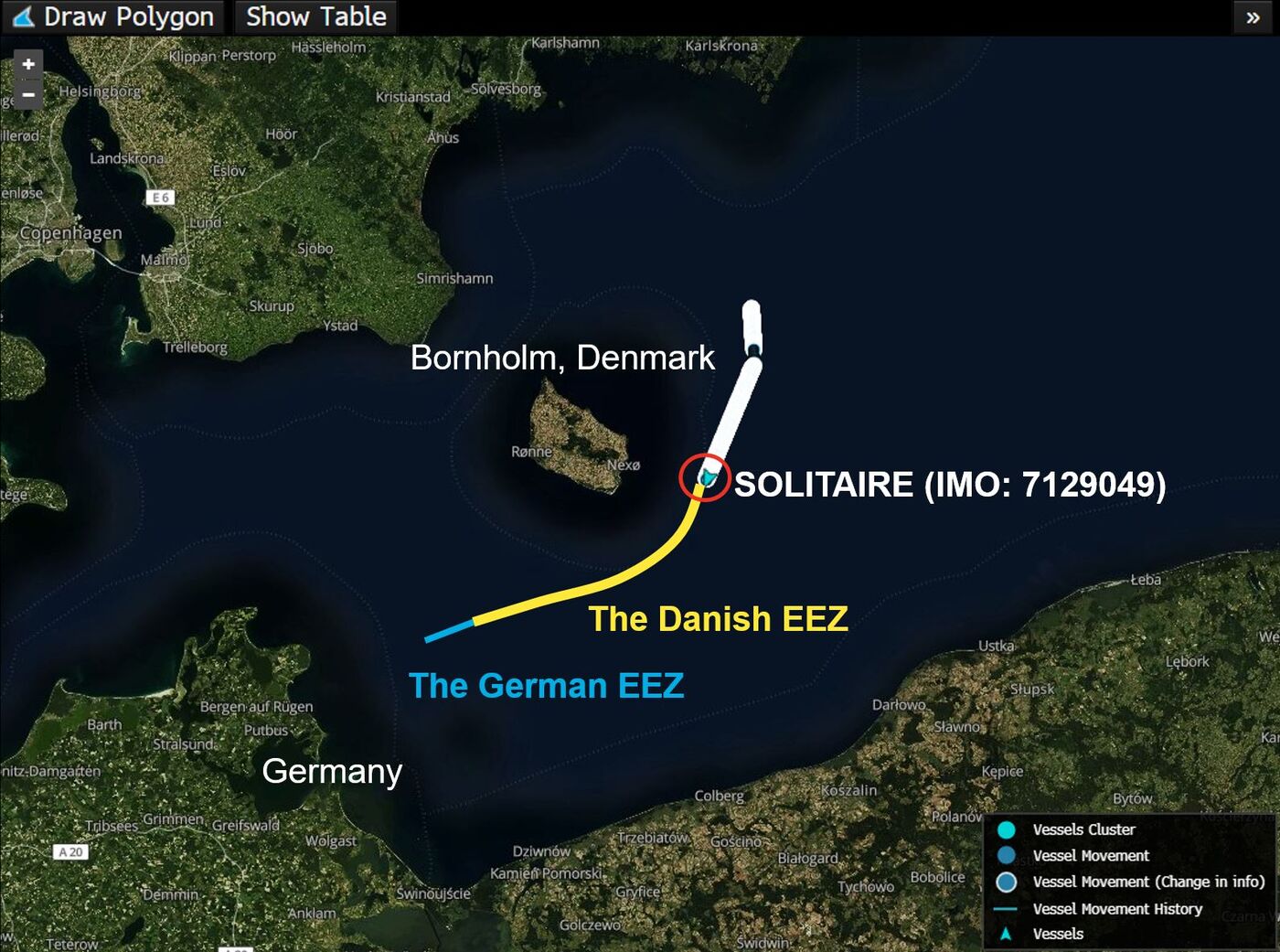

Some 350 companies are involved in building the undersea link, most notably the Swiss company Allseas Group SA, whose ships are laying the last section of pipe in Danish waters.

The sanctions targets vessels that lay the pipeline as well as executives from companies linked to those ships. They could be denied visas and have transactions related to their U.S.-based property or interests blocked.

The sanctions bill includes a 30-day “wind-down period” that allows targeted companies to halt their operations after the law comes into effect. That could give Gazprom just enough time to finish work.

The last section of pipe can be completed by about Jan. 11, well before the end of the period, according to Anna Borisova, an analyst at BloombergNEF in London. Nord Stream 2 will be in a position to be commissioned between April and June 2020, after additional connection work and testing, she said.

“The project seems safe,” Borisova said. “We don’t see major risks.”

White line indicates the path the Solitaire pipe lay vessel has taken in the past few weeks. The yellow line shows the route Nord Stream 2 will follow thorough Danish waters.

Source: Ship tracking data and BloombergNEF

The new pipeline is set to ship as much as 55 billion cubic meters of Russian gas annually directly to Germany, doubling capacities of the existing Nord Stream link. The U.S. and Eastern European nations see it as a threat to the Ukrainian transit route that has been in place for decades, bringing revenues to the smaller Former Soviet Union nation. The new link theoretically gives Russia the ability to bypass Ukraine as a transit corridor.

The completion of Nord Stream 2 could would bring fresh supplies of gas to Europe’s already glutted market. That would make it more difficult for the U.S. to gain a bigger foothold in shipping cargoes of liquefied natural gas by tanker into Europe.

U.S. sales of the fuel made up 26% of imports in November. Flexible terms for contracts from U.S. producers mean that they will sell to where prices are highest, meaning more cargoes may head to Asia in the coming months.

Beyer recognized the need for Europe to buy the fuel from a wider range of sellers.

“From a European standpoint, not only German, we need to diversify our energy interests,” he said. “We are also interested in receiving LNG from the United States of America.”

Source: Bloomberg