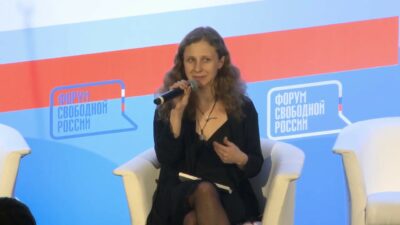

The co-chairman of the Memorial Human Rights Center spoke at a session of the UN Human Rights Council

According to Sergei Davidis, there are about 700 people on Memorial’s lists of political prisoners today, but this number is only the minimum proven number of people illegally imprisoned for political reasons. OVD-Info estimates that more than 1,100 people are currently imprisoned for political reasons. The real number is many times higher, as there is insufficient information on many cases and entire categories of cases.

The scope and cruelty of repressions have multiplied with the beginning of the full-scale war.

The most obvious target of persecution is people with an anti-war stance. No less than 250 such people were deprived of their liberty. Those who wrote about the war at least in their blog, with a minimum of readers, something different from the official position, those who reported war crimes, condemned aggression or even simply called the war a war, and not “SMO” as prescribed, are persecuted. Even more inadequately brutalized are those who took any active action to protest the war, regardless of its actual consequences. All the more persecuted are those who express support for Ukraine in some form. This applies both to statements and to the provision of assistance to Ukraine, and even to the alleged intention to provide it.

The number of those deprived of liberty in connection with the exercise of the right to freedom of conscience is in the hundreds (417), including Jehovah’s Witnesses and representatives of various peaceful Muslim groups, including more than a hundred Crimean Tatars. The persecution of those who evade participation in the war has become widespread. Several thousand people have already been subjected to such persecution.

The Russian authorities have shown no less scope and cruelty in their persecution of Ukrainians, both prisoners of war and civilians.

Hundreds of prisoners of war are being prosecuted both on completely unconvincing charges of war crimes and even on charges of serving in units that the Russian authorities have arbitrarily and unjustifiably declared terrorist. At least 7,000 civilians abducted from the territory of Ukraine are being held incommunicado, contrary to the requirements of not only international but also Russian law. Dozens of articles of the Criminal Code are being used as instruments of political criminal repression. Among them there are frankly illegal norms, for example, providing for punishment for so-called discrediting the use of the Armed Forces or dissemination of knowingly false information about such use, norms related to undesirable organizations and foreign agents. Thus, discrediting the use of the army means any negative opinion of a citizen about the aggressive war unleashed by Putin.

The majority of political repressions are carried out on the basis of norms that appear to be permissible in a democratic society, but in practice are applied arbitrarily or unacceptably broadly.

This applies primarily to a set of articles of the Criminal Code related to extremism and terrorism. A special role here is played by the accusation of calls to terrorism or its justification, which is understood, for example, as any expression of support and sympathy for the armed forces of Ukraine.

More than a hundred people have been imprisoned on secret charges of state treason, the composition of which has been significantly expanded and the punishment increased to life imprisonment.

Not the most massive, but an important and growing part of repression is ideological repression, the most striking example of which are cases of so-called rehabilitation of Nazism or insulting the feelings of believers. The growing scale of repression is, on the one hand, a natural feature of the military-police dictatorship established in Russia. On the other hand, it is the regime’s response to the ongoing protest of citizens, despite threats and risks. Repression is aimed both at isolating those people whom the regime sees as a threat and at intimidating society as a whole through demonstrative persecution of sometimes even random people.

Political repression is the foundation of Putin’s regime and a necessary condition for the continuation of the war.

In turn, support for political prisoners and solidarity with them have become, to a large extent, the framework around which Russian civil society unites both inside and outside Russia. Attention to and support for Russian political prisoners is important not only for humanitarian and legal reasons, but also because supporting them is supporting Russian civil society and countering the efforts of Putin’s dictatorship.

It is also important to talk about Russian political prisoners today so that after the war is over, the demand for the release of political prisoners becomes a condition for any settlement, any easing of sanctions pressure on Putin’s regime.