Chess and human rights champion Garry Kasparov gives Kyiv Post an exclusive interview after Russia designates his Free Russia Forum as a “threat to the constitutional order and security.”

“Well, it’s about time!” laughs Kasparov, responding to how he takes the news that his Free Russia Forum, based in Vilnius, Lithuania, was deemed as a “threat to the constitutional order and security” by the Russian General Prosecutor’s Office.

Freshly arrived home from a tour of Europe, where he had been pushing for wider sanctions against the “Putin Regime and its enablers,” Kasparov sounds energetic and keen to discuss his upcoming plans to support Ukraine.

Kasparov, who has been an outspoken supporter of democracy and human rights worldwide, has not been quiet about the war in Ukraine. Unlike some in the Russian democratic opposition, Free Russia Forum, which he founded in 2016, has always had as a tenet that to be a member of the organization, one must reject the illegal occupation of Ukraine’s Crimea and Donbas.

Kasparov, personally, has gone even further and takes an active role in traversing the globe to meet with high-level officials across Europe and the U.S. to identify new ways in which sanctions can be implemented against Russia and military support given to Ukraine.

This active approach, using his fame and high profile to reach the global levers of power to assist in thwarting Putin, has captured the eye of not only the Russian General Prosecutor’s Office, but also of global leaders.

On Feb 2, the Munich Security Forum, often called the “Davos of Defense,” announced that in addition to not inviting Russian officials to the event, they would be inviting Kasparov and his long-time ally in the fight for democracy in Russia, Mikhail Khodorkovsky.

Khodorkovsky, like Kasparov, has been in the democratic opposition to Putin since long before many got on the “stop Putin bandwagon.”

Khodorkovsky, formerly an executive of Russia’s largest oil company, was held in prison for a decade under what the international community decried as politically motivated charges. In 2013, following increased international pressure, Khodorkovsky was pardoned by Putin. Since then, the former prisoner has dedicated himself to initiatives to oppose the Putin Regime.

Ivan Tyutrin, who helped to establish the Free Russia Forum, sees the Russian Prosecutor’s actions as “a good sign.” He said, “It is proof that we are doing good work. We are creating problems for the regime. However, we were prepared for this to happen.”

But why do Russian authorities routinely go to such lengths to slow down the Free Russia Forum? Chuckling, Tyutrin retorts that “they correctly consider us to be their enemies.”

Kasparov thinks that the Russian General Prosecutor’s persecution of his organization, this time, was just a matter of time as Russian authorities are “so alarmed because of what we [Kasparov and Khodorkovsky] said in Foreign Affairs: we offered a real plan to get Russia out of the Putin abyss and what to do for the future. They worry about the power of our arguments.”

The Chess Grandmaster is referring to his Jan. 23, 2023 piece in Foreign Affairs, a strongly worded thesis arguing that “Putin’s effort to restore Russia’s lost empire is destined to fail. The moment is therefore ripe for a transition to democracy and a devolution of power to the regional levels. But for such a political transformation to take place, Putin must be defeated militarily in Ukraine. A decisive loss on the battlefield would pierce Putin’s aura of invincibility and expose him as the architect of a failing state, making his regime vulnerable to challenge from within.”

Russian authorities were likely less than enthralled to read that Kasparov and Khodorkovsky, in one of the world’s premier journals of international affairs, called for Putin to not only lose in Ukraine, but to lay out a plan following Putin’s demise that would include signing “a peace agreement with Ukraine, recognizing the country’s 1991 borders and justly compensating it for the damage caused by Putin’s war.”

If things work out as the duo hopes, from there all of Putin’s dreams would further collapse as they argue that a post-Putin Russia would need to “reject the imperial policies of the Putin regime, both within Russia and abroad, including by ceasing all formal and informal support for pro-Russian entities in the countries of the former Soviet Union,” and then to “begin to demilitarize Russia.”

Tyutrin agrees with Kasparov and Khodorkovsky’s analysis: “We see that there is a huge irrational fear in the West of what will happen after Putin: Will it create instability? Will Russia’s nukes be loose? But we are prepared for a Putin-less world.”

He adds that for “seven years the Free Russia Forum has a clear plan that we will seek federalization, demilitarization, de-occupation of all Russian-occupied lands… this is the target we have. We are all aiming for this.”

Kasparov has no regrets about his article or the fallout it has received from an unhappy Kremlin or those in the Russian democratic opposition who do not see eye-to-eye with his view. Rather, Kasparov says in response that others in the opposition “talk about the future of Russia in vague terms,” however, “we are talking in specific details – and that is a threat to the Putin regime.”

There are risks that come with espousing such views, the human rights advocate reflects, recalling his former ally and friend, Boris Nemtsov, who was gunned down outside of the Kremlin in 2015.

Asked if he might want to wrap up the interview after the tiring transatlantic flight, Kasparov laughed, “Rest? You’re kidding, right? I can do that later – I have just sat down to work and have hours more to do today.”

Does Kasparov not see a paradox in the fact that he considers himself a “patriot of Russia’” while calling on the U.S. and Europe to give Ukraine more weapons in order to kill Putin’s soldiers with greater efficiency?

“No, quite the contrary,” he says, “we believe that every true patriot of Russia should be focused on helping Ukraine to win.”

Observers have noted that many who oppose Putin, do not necessarily support Ukraine. Kasparov calls them out by recalling that “you still have the majority of the Russian opposition saying ‘stop the war.’ In our eyes, that means nothing.”

If “stop the war” means nothing, then what should a “patriotic Russian” want?

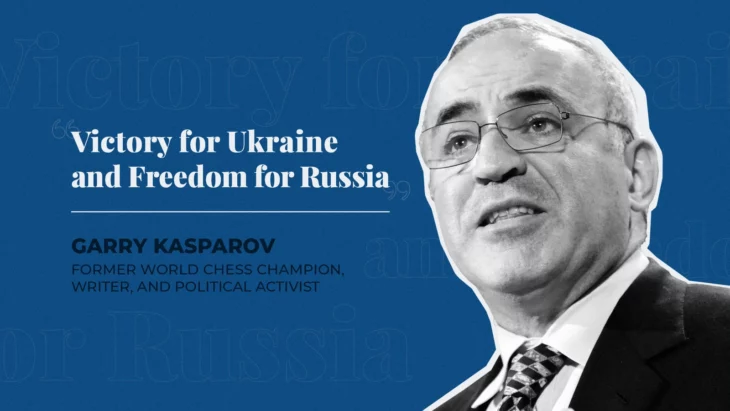

“In our eyes, victory for Ukraine and freedom for Russia are linked events,” Kasparov says.