How Russian spies hacked the Justice, State, Treasury, Energy and Commerce Departments

Bill Whitaker reports on how Russian spies used a popular piece of software to unleash a virus that spread to 18,000 government and private computer networks.

President Biden inherited a lot of intractable problems, but perhaps none is as disruptive as the cyber war between the United States and Russia simmering largely under the radar. Last March, with the coronavirus spreading uncontrollably across the United States, Russian cyber soldiers released their own contagion by sabotaging a tiny piece of computer code buried in a popular piece of software called “SolarWinds.” The hidden virus spread to 18,000 government and private computer networks by way of one of those software updates we all take for granted. The attack was unprecedented in audacity and scope. Russian spies went rummaging through the digital files of the U.S. departments of Justice, State, Treasury, Energy, and Commerce and for nine months had unfettered access to top-level communications, court documents, even nuclear secrets. And by all accounts, it’s still going on.

Brad Smith: I think from a software engineering perspective, it’s probably fair to say that this is the largest and most sophisticated attack the world has ever seen.

Brad Smith is president of Microsoft. He learned about the hack after the presidential election this past November. By that time, the stealthy intruders had spread throughout the tech giants’ computer network and stolen some of its proprietary source code used to build its software products. More alarming: how the hackers got in… piggy-backing on a piece of third party software used to connect, manage and monitor computer networks.

Bill Whitaker: What makes this so momentous?

Brad Smith: One of the really disconcerting aspects of this attack was the widespread and indiscriminate nature of it. What this attacker did was identify network management software from a company called SolarWinds. They installed malware into an update for a SolarWinds product. When that update went out to 18,000 organizations around the world, so did this malware.

“SolarWinds Orion” is one of the most ubiquitous software products you probably never heard of, but to thousands of I.T. departments worldwide, it’s indispensable. It’s made up of millions of lines of computer code. 4,032 of them were clandestinely re-written and distributed to customers in a routine update, opening up a secret backdoor to the 18,000 infected networks. Microsoft has assigned 500 engineers to dig in to the attack. One compared it to a Rembrandt painting, the closer they looked, the more details emerged.

Brad Smith: When we analyzed everything that we saw at Microsoft, we asked ourselves how many engineers have probably worked on these attacks. And the answer we came to was, well, certainly more than 1,000.

Bill Whitaker: You guys are Microsoft. How did Microsoft miss this?

Brad Smith: I think that when you look at the sophistication of this attacker there’s an asymmetric advantage for somebody playing offense.

Bill Whitaker: Is it still going on?

Brad Smith: Almost certainly, these attacks are continuing.

The world still might not know about the hack if not for FireEye, a three-and-a-half billion dollar cybersecurity company run by Kevin Mandia, a former Air Force intelligence officer.

Kevin Mandia: I can tell you this, if we didn’t do investigations for a living, we wouldn’t have found this. It takes a very special skill set to reverse engineer a whole platform that’s written by bad guys to never be found.

FireEye’s core mission is to hunt, find, and expel cyber intruders from the computer networks of their clients – mostly governments and major companies. But FireEye used SolarWinds software, which turned the cyber hunter into the prey. This past November, one alert FireEye employee noticed something amiss.

Kevin Mandia: Just like everybody working from home, we have two-factor authentication. A code pops up on our phone. We have to type in that code. And then we can log in. A FireEye employee was logging in, but the difference was our security staff looked at the login and we noticed that individual had two phones registered to their name. So our security employee called that person up and we asked, “Hey, did you actually register a second device on our network?” And our employee said, “No. It wasn’t, it wasn’t me.”

Suspicious, FireEye turned its gaze inward, and saw intruders impersonating its employees snooping around inside their network, stealing FireEye’s proprietary tools to test its clients defenses and intelligence reports on active cyber threats. The hackers left no evidence of how they broke in – no phishing expeditions, no malware.

Bill Whitaker: So how did you trace this back to SolarWinds software?

Kevin Mandia: It was not easy. We took a lotta people and said, “Turn every rock over. Look in every machine and find any trace of suspicious activity.” What kept coming back was the earliest evidence of compromise is the SolarWinds system. We finally decided: Tear the thing apart.

They discovered the malware inside SolarWinds and on December 13 informed the world of the brazen attack.

Much of the damage had already been done. The U.S. Justice Department acknowledged the Russians spent months inside their computers accessing email traffic – but the department won’t tell us exactly what was taken. It’s the same at Treasury, Commerce, the NIH, Energy. Even the agency that protects and transports our nuclear arsenal. The hackers also hit the biggest names in high tech.

Bill Whitaker: So, what does that target list tell you?

Brad Smith: I think this target list tells us that this is clearly a foreign intelligence agency. It exposes the secrets potentially of the United States and other governments as well as private companies. I don’t think anyone knows for certain how all of this information will be used. But we do know this: It is in the wrong hands.

And Microsoft’s Brad Smith told us it’s almost certain the hackers created additional backdoors and spread to other networks.

The revelation this past December came at a fraught time in the U.S. President Trump was disputing the election, and tweeted China might be responsible for the hack. Within hours he was contradicted by his own secretary of state and attorney general. They blamed Russia. The Department of Homeland Security, FBI and intelligence agencies concurred. The prime suspect: the SVR, one of several Russian spy agencies the U.S. labels “advanced persistent threats.” Russia denies it was involved.

Brad Smith: I do think this was an act of recklessness. The world runs on software. It runs on information technology. But it can’t run with confidence if major governments are disrupting and attacking the software supply chain in this way.

Bill Whitaker: That almost sounds like you think that they went in to foment chaos?

Brad Smith: What we are seeing is the first use of this supply chain disruption tactic against the United States. But it’s not the first time we’ve witnessed it. The Russian government really developed this tactic in Ukraine.

For years the Russians have tested their cyber weapons on Ukraine. NotPetya, a 2017 attack by the GRU, Russia’s military spy agency, used the same tactics as the SolarWinds attack, sabotaging a widely-used piece of software to break into thousands of Ukraine’s networks, but instead of spying – it ordered devices to self-destruct.

Brad Smith: It literally damaged more than 10% of that nation’s computers in a single day. The television stations couldn’t produce their shows because they relied on computers. Automated teller machines stopped working. Grocery stores couldn’t take a credit card. Now, what we saw with this attack was something that was more targeted, but it just shows how if you engage in this kind of tactic, you can unleash an enormous amount of damage and havoc.

Bill Whitaker: It’s hard to downplay the severity of this.

Chris Inglis: It is hard to downplay the severity of this. Because it’s only a stone’s throw from a computer network attack.

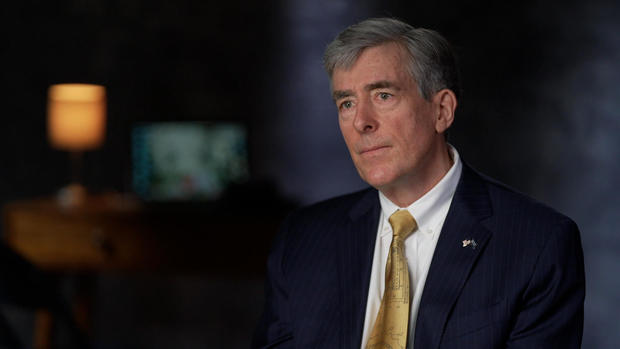

Chris Inglis spent 28 years commanding the nation’s best cyber warriors at the National Security Agency – seven as its deputy director – and now sits on the Cyberspace Solarium Commission – created by Congress to come up with new ideas to defend our digital domain.

Bill Whitaker: Why didn’t the government detect this?

Chris Inglis: The government is not looking on private sector networks. It doesn’t surveil private sector networks. That’s a responsibility that’s given over to the private sector. FireEye found it on theirs, many others did not. The government did not find it on their network, so that’s a disappointment.

Disappointment is an understatement. The Department of Homeland Security spent billions on a program called “Einstein” to detect cyber attacks on government agencies. The Russians outsmarted it. They circumvented the NSA, which gathers intelligence overseas, but is prohibited from surveilling U.S. computer networks. So the Russians launched their attacks from servers set up anonymously in the United States.

Bill Whitaker: This hack happened on American soil. It went through networks based in the United States. Are our defense capabilities constrained?

Chris Inglis: U.S. Intelligence Community, U.S. Department of Defense, can suggest what the intentions of other nations are based upon what they learn in their rightful work overseas. But they can’t turn around and focus their unblinking eye on the domestic infrastructure. That winds up making it more difficult for us.

He says history shows that once inside a network, the Russians are a stubborn adversary.

Chris Inglis: It’s hard to kind of get something like this completely out of the system. And they certainly don’t understand all the places that it’s gone to, all of the manifestations of where this virus, where this software still lives. And that’s gonna take some time. And the only way you’ll have absolute confidence that you’ve gotten rid of it is to get rid of the hardware, to get rid of the systems.

Bill Whitaker: Wow. So unless you get rid of all the computers and all the computer networks, you will not be sure that you have gotten this out of the systems.

Chris Inglis: You will not be.

Jon Miller: We’ve never been left with a breach like that before where we know months into it that we’re only looking at the tip of the iceberg.

It’s not everyday you meet someone who builds cyber weapons as complex as those deployed by Russian intelligence. But Jon Miller, who started off as a hacker and now runs a company called Boldend, designs and sells cutting-edge cyber weapons to U.S. intelligence agencies.

Jon Miller: I build things much more sophisticated than this. What’s impressive is the scope of it. This is a watershed style attack. I would never do something like this. It creates too much damage.

Miller says with the SolarWinds attack, Russia has demonstrated that none of the software we take for granted is truly safe, including the apps on our telephones, laptops, and tablets. These days, he says, any device can be sabotaged.

Jon Miller: When you buy something from a tech company, a new phone or a laptop, you trust that that is secure when they give it to you. And what they’ve shown us in this attack is that is not the case. They have the ability to compromise those supply chains and manipulate whatever they want. Whether it’s financial data, source code, the functionality of these products. They can take control.

Bill Whitaker: So, for instance, they could destroy all the computers on a network?

Jon Miller: Oh, easily. The malware that they deployed off of SolarWinds, it didn’t have the functionality in it to do that. But to do that is trivial. Couple dozen lines of code.

Bill Whitaker: And there’re still some companies that don’t yet know they were breached?

Jon Miller: It’s still ongoing. New companies are getting breached. We’ll see new companies breached today that weren’t breached this morning. Where it’s different in a lot of ways is normally when you catch someone in the act, they stop. That’s not the case with this breach.

Produced by Graham Messick and Jack Weingart. Broadcast associate, Emilio Almonte. Edited by Michael Mongulla.