- Russia has been keeping relatively quiet on the global stage of late, particularly as it has issues closer to home to focus on including political reforms and economic revival, but make no mistake about it, the country’s influence across the world is far-reaching and important.

Russia has been keeping relatively quiet on the global stage of late, particularly as it has issues closer to home to focus on including political reforms and economic revival, but make no mistake about it, the country’s influence across the world is far-reaching and important.

Russia might display a foreign policy approach in which it doesn’t appear to want to “interfere” in the domestic affairs of other nations or to see regime change; In January in his State of the Nation address, President Vladimir Putin insisted that “we don’t want to impose our point of view on anyone.”

Nonetheless, similarly to other superpowers like the U.S. and China, Russia has spread its economic and geopolitical influence by supporting (and indeed, propping up) rulers and regimes, like Syria’s Bashar Assad, or plowing money into infrastructure projects (like energy infrastructure in Europe) and by giving both tacit and overt military and economic support to other states around the world, as seen in Venezuela.

It matters where Russia chooses to intervene, invest, “interfere” and even annex because its influence is a direct challenge to the West, or more specifically, the U.S. It is also a way to allay the humiliation of the past, experts say.

“The U.S. and China are competing for economic dominance; meanwhile, Russia is asserting its role on the geopolitical stage, where it wants to compete on a par with the U.S.,” Agathe Demarais, global forecasting director at The Economist Intelligence Unit, told CNBC.

“For Russia, being present on the global stage and defending what it considers as its backyard represent crucial steps to overcoming the humiliation that the country perceived that it suffered after the Soviet Union collapsed and the U.S. was left as the sole global superpower.”

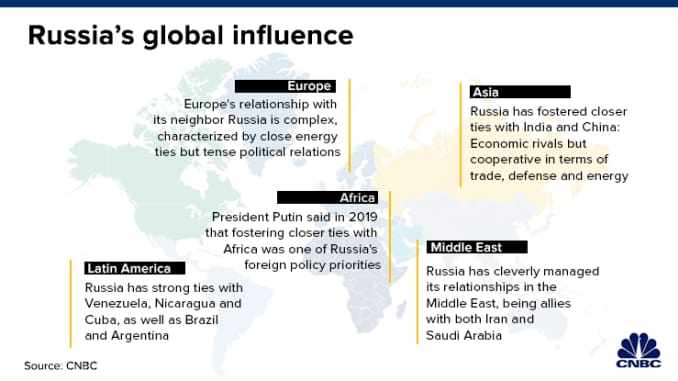

Here are the regions that Russia is invested in, both politically and economically:

Latin America

Unsurprisingly for a country that has a long history of Communist rule in the 20th century, Russia has had long ties with several Latin American states that have socialist or communist regimes, like Venezuela, Nicaragua and Cuba.

It has sought to develop these relationships largely with diplomatic support, arms sales and energy investments. But it has also recently strengthened economic and political ties with regional powers Argentina, Mexico and Brazil.

Nonetheless, Russia’s relationship with Venezuela is the most prominent, and antagonizing, for the West. Russia has long supported the regime of Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro and has been seen as a key power propping up the socialist government, helping to ward off a U.S.-supported coup led by opposition leader Juan Guaido in 2019.

Russia has also supported Venezuela on the military and economic front; Caracas is believed to have bought billions of dollars’ worth of weapons from Russia, paid for with loans from Russia, whose state oil company Rosneft has also invested heavily in Venezuela’s state oil company, Petróleos de Venezuela, or PDVSA.

Russia’s government and Rosneft have given Venezuela at least $17 billion in loans and credit lines since 2006, according to Reuters calculations. Russia restructured Venezuela’s debt in 2017, to allow it more manageable repayments.

“Russia is Venezuela’s main geopolitical ally and has also established considerable economic ties in the country, particularly in areas such as energy and defense. The energy sector saw investments by many of Russia’s main oil and gas companies, such as Gazprom, Rosneft, and Lukoil, but Russia’s involvement in armaments has been more heavily publicized,” the EIU’s Demarais told CNBC Tuesday.

However, she noted that “Russia’s economic involvement in Venezuela, unlike China’s, has paled against its political investment in securing the survival of the Maduro regime.”

This has largely been part of a broader geo-strategic interest of challenging the U.S. in different parts of the world, she said, and, “given the Chávez/Maduro government’s anti-American rhetoric, this was a natural beachhead for Russian interests in the West.”

She said proof that Moscow views its relationship with Venezuela mostly along geopolitical lines is the fact that Venezuela still has considerable unpaid financial obligations to Russia, of around $3 billion.

As U.S. sanctions (that Russia calls illegal) continue to bite, Russia continues to support Venezuela and on Friday, Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov visited the country.

Lavrov’s visit, which was preceded by trips to Cuba and Mexico, was also a show of defiance against U.S. sanctions, something that Russia knows all about given international sanctions on the country for its own misdemeanors including its annexation of Crimea from Ukraine and meddling in the 2016 U.S. election.

The foreign minister met Maduro and other top ministers to discuss deeper cooperation on energy, mining, transport, agriculture and defense, as well as discussing steps “to counteract illegal unilateral sanctions.”

Africa

Europe, the U.S. and China’s investments in, and aid to, Africa are well established but what’s less well known is that Russia had a strong influence in the continent during Soviet times, but this waned following the collapse of the union in 1991.

With China forming investment partnerships around the world, and particularly Africa, as part of its Belt and Road Initiative, widely seen as a way for China to increase its global influence and economic reach, Russia looks keen to increase its own trade relations with Africa and access the country’s vast mineral wealth and grab commercial opportunities.

In October 2019, President Vladimir Putin hosted a Russia-Africa summit and economic forum for over 40 African heads of state in the Black Sea resort of Sochi. Ahead of the summit, Putin told TASS news agency that only Russia would respect the sovereignty of African governments and he played on the long history of relations.

“We see how an array of Western countries are resorting to pressure, intimidation and blackmail of sovereign African governments,” Putin said, adding that Russia was ready to provide help without “political or other conditions.”

“Our country played a significant role in the liberation of the continent, contributing to the struggle of the peoples of Africa against colonialism, racism and apartheid,” he said. “Although ties deteriorated after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, traces remain: the Mozambique flag, for instance, carries the Kalashnikov rifle.”

At the summit, Putin said Russia’s trade with Africa in 2018 amounted to over $20 billion, having doubled in the previous five years, but that the aim was to increase this. “We believe that trade, economic and investment cooperation is an important element in Russia’s relations with African countries,” Putin told the audience.

Daragh McDowell, head of Europe and Central Asia at Verisk Maplecroft, is not convinced that the Russian state’s reach in Africa is that extensive, arguing that private Russian companies had done well in the continent, such as those connected to the military contractor Wagner Group and linked to Russian businessman and a close associate of Putin, Yevgeny Prigozhin.

“From what I can see of the engagement in Africa, a number of individuals and companies — particularly those connected to Yevgeny Prigozhin and (the) Wagner group — have done very well out of mineral concessions, but I’m not sure that I’d call that a win for the Russian state, per se. Then again, the use of deniable, private sector mercenary firms means that the Russian state is, on paper at least, not really putting much in,” he said.

The success of private firms then allowed the Russian foreign ministry to follow “in the wake of a successful engagement to trumpet the foreign policy ‘success’,” McDowell told CNBC.

Middle East

Russia has rapidly expanded its geopolitical and military ties in the Middle East in the last decade, not only with Syria but with the region’s most powerful kingdom, Saudi Arabia, particularly (but not only) in terms of the OPEC alliance with Russia and other non-OPEC producers to limit oil output in a bid to stabilize oil prices.

In fact, Russia is one of the few countries that has managed to have good relations with both Saudi Arabia and its arch nemesis, Iran. Russia has repeatedly criticized the U.S.′ re-imposition of sanctions on Iran following its withdrawal from the 2015 nuclear deal.

Aside from Russia’s relationships with fellow oil producers, which could be expected, its relationship with Syria is perhaps the most infamous one it has in the region.

Russia’s military presence in Syria and support for Assad came to the fore in recent years during the allied campaign against the terrorist group Islamic State, on the one hand, and preventing the attempts of rebel forces in a civil war trying to overthrow the Assad regime, on the other. Russia has repeatedly said it does not want to see regime change in Syria.

Russia’s support is seen as a way for the country to expand and maintain its influence in the Middle East; it has also benefited from a U.S. administration under President Donald Trump that does not want “boots on the ground” in the Middle East (although it appears keen to still shape government policy, most recently seen in Trump’s peace plan for Israel and Palestine).

The EIU’s Demarais noted how “in many African and Middle East countries, Russia seeks to use the vacuum left by the U.S. to fulfill the objective of increasing its global presence. Russia also seeks to capitalize on popular disenchantment with controversial U.S. policies, such as relocating the US embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem, and brands itself as a reliable, alternative power,” she said.

Europe

Russia’s relationship with its closest neighbor Europe is complicated. While it has appeared to foment and exploit divisions in the EU by giving its support to right-wing and populist movements in the region, it has also undertaken massive joint infrastructure projects with European countries and companies, such as the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline with Germany, on which the U.S. recently imposed sanctions.

On the more problematic side of Russia’s relationship with Europe, Putin has met with leaders of the region’s more ideologically extreme parties who are seen as potential threats to the EU project, including Marine Le Pen who leads the nationalist National Rally party and Hungary’s Prime Minister Viktor Orban. Italy’s right-wing Lega party has also reportedly held meetings with Russia’s top brass.

What those parties and politicians share is the kind of euroskepticism that has led to unprecedented political upheaval, like the U.K.’s departure from the EU. There has, in fact, been an investigation into possible Russian interference in the 2016 referendum, but the report has not yet been published.

Perhaps the biggest issue for Europe is how Russia has treated an aspiring EU and NATO member, Ukraine, by annexing Crimea in 2014 and for its role in a pro-Russian uprising in the east of Ukraine that is still unresolved. Russia is still subject to international sanctions for these actions although support for sanctions is low among some EU members.

There have been some concerns in other former Soviet states, like the Baltic nations Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia, that a resurgent Russia could provoke a military confrontation or even invade, particularly given the sizable minority of ethnic Russians still living in those countries since the Soviet Union collapsed.

Concerns have led to NATO stationing more troops in the Baltic states (and Poland) to act as a deterrent to Russia, who has made the Baltic states nervous in light of some provocative military exercises and maneuvers it has carried out in the Baltic Sea or in airspace close to the Baltic nations — often prompting NATO jets to be scrambled to investigate.

But close watchers of Russian politics say it’s very unlikely that Russia would ever provoke an actual conflict in its former territories, however.

“I think this fear of Russia possible invading the Baltic states is completely overdone and irrational,” Jacob Grapengiesser, partner & head of Eastern Europe at asset manager East Capital, and based in Moscow for the last 20 years, told CNBC Wednesday.

“I just think Russia wants to be respected and seen. Don’t forget their history: For much of the nineties, they were really down on their knees and now they’re upstanding and doing relatively well. So, I think you need to see it in that light. This is why they fly their planes and invest in new weapons and they just want to show that they are someone.”

“But I think they have no intentions of taking it further than that by some sort of invasion,” he said.

Other countries that were also part of the Soviet Union — those in the Caucasus which include Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia — have a checkered relationship with Russia. While relations between Moscow and Georgia remain strained following a military conflict between the countries in 2008 (there were anti-Russian protests in the capital Tbilisi in 2019) those between Russia and Azerbaijan have improved.

In December, Putin wished his Azerbaijani counterpart Ilham Aliyev a happy birthday and said “it is hard to overestimate your personal contribution to consolidating the strategic partnership between our two countries. I genuinely value the trust and mutual understanding that has developed between us.”

What does it mean for the West?

Experts diverge on how extensive and influential Russia actually is abroad. Verisk Maplecroft’s Daragh McDowell told CNBC that “a lot of Russia’s foreign policy is based on bluffing and good PR.”

“Moscow can dispatch mercenaries to prop up certain governments, provide political advice etc. but it simply doesn’t have the capacity or resources to turn this into long-term influence except in a handful of cases (primarily Syria and Venezuela) and even then it tends to be dependent upon particular political actors or factions without the kind of deeper ‘roots’ needed to ensure the relationship endures when the personalities change,” he said Tuesday.

“They also can’t provide the level of investment and development assistance that countries like China can, which is a much more robust strategic competitor for the West.”

McDowell made the important distinction between Russian companies’ influence in other countries, and the Russian state too.

“From what I can see of the engagement in Africa a number of individuals and companies … have done very well out of mineral concessions, but I’m not sure that I’d call that a win for the Russian state, per se,” he said.

“Then again, the use of deniable, private sector mercenary firms means that the Russian state is, on paper at least, not really putting much in. It is more that certain individuals and groups are allowed to market their services as mercenaries in Africa, with the Russian foreign ministry following in the wake of a successful engagement to trumpet the foreign policy ‘success’,” he noted.

—CNBC’s Crystal Mercedes and John Schoen contributed to this report.