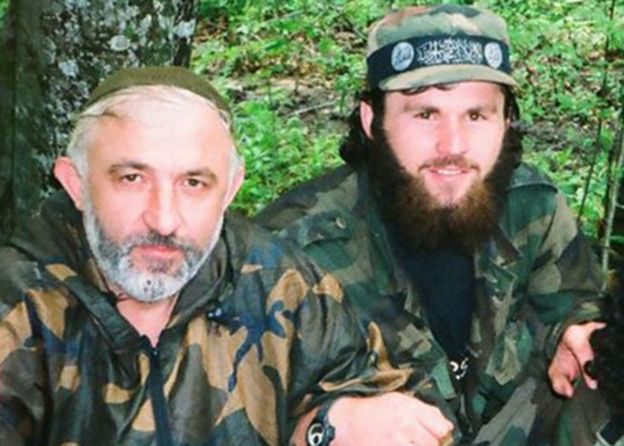

The violent death of a former Chechen rebel commander at the hands of a man suspected to be a Russia-backed assassin in a Berlin park has shocked and outraged many Germans.

Zelimkhan Khangoshvili was shot in the head in broad daylight in August.

Germany’s most senior prosecutor believes the evidence points to a cold-blooded contract killing on German soil, ordered either by authorities in Russia or its Chechen republic.

In custody is a suspect who travelled from Russia shortly before the killing.

Chancellor Angela Merkel is not known for impassioned public outbursts. But, even as her government expelled two Russian diplomats over the murder, there were perhaps other reasons for her restraint, as she answered reporters’ questions at the end of Wednesday’s Nato summit in London.

She intended, she said, to bring up the case with Russian President Vladimir Putin when she met him in Paris next week. The expulsion of the diplomats was a response to Russia’s refusal to help with the ongoing investigation, she added.

Image copyrightFACEBOOK

Image copyrightFACEBOOKThe revelations about the Berlin killing come at a sensitive time.

The two leaders are due to meet on Monday, alongside the French and Ukrainian presidents, to de-escalate the conflict in eastern Ukraine.

There has, to date, been little progress. This is the first time in three years that the parties have agreed to meet as part of the so-called Normandy format.

Mrs Merkel who, together with former French President François Hollande, initiated the format, is keen for a successful outcome.

Many have drawn comparisons between the Berlin case and that of the March 2018 Skripal poisoning in the UK, when former double agent Sergei Skripal and his daughter Yulia were attacked with a nerve agent. A 44-year-old woman died after coming into contact with the nerve agent.

But calls for further action against Russia, while they exist, are rather more muted in Germany than they were in the UK.

Take Roderick Kiesewetter, a senior MP from Angela Merkel’s CDU party, who condemned Russia’s refusal to help with German investigations, but also says that he doesn’t expect an escalation and that the two countries will “continue to have a reasonable relationship”.

Image copyrightEPA

Image copyrightEPAThe somewhat measured response is due, in part, to Angela Merkel’s leadership style. But it’s also to do with the relationship between Berlin and Moscow, which is as complex as it is contradictory.

Mrs Merkel, for example, was swift to condemn Russia’s 2014 annexation of Crimea, and has defended EU sanctions against Moscow ever since.

But she has also championed, despite opposition at home and further afield, the Nord Stream 2 pipeline, which will double the amount of Russian gas coming into Europe via Germany.

Entwined by their overlapping histories, Germany and Russia are close in some respects – economically, geographically and socially.

Thousands of German companies do business with Russia and some lobby against sanctions, which they argue cripple trade.

A recent survey found that one in three Germans have a positive view of Russia. That figure is higher in the old east of the country, once the Soviet-controlled German Democratic Republic.

Image copyrightAFP

Image copyrightAFPAngela Merkel and Vladimir Putin are products of that shared history.

The Russian president, then a young KGB officer, was stationed in Dresden, living in the GDR where Angela Merkel was forging a career as a young scientist. He speaks some German, she some Russian.

It is 12 years since Mr Putin, knowing that she feared dogs, let his black Labrador gate-crash one of his early meetings with the German chancellor.

These days, he is said to have a grudging respect for the woman who has emerged to be, like him, one of the continent’s longest-serving leaders. And she has forged a reputation as the West’s interlocutor with the Russian leader.

It won’t be the first time Mrs Merkel confronts the Russian president.

Few expect that she’ll get answers to her questions about the killing in Berlin’s Kleiner Tiergarten park.

But she knows that this meeting comes as the EU is itself unsure, divided even, over how to shape its future relationship with Russia. And Vladimir Putin knows it too.

Source: BBC